|

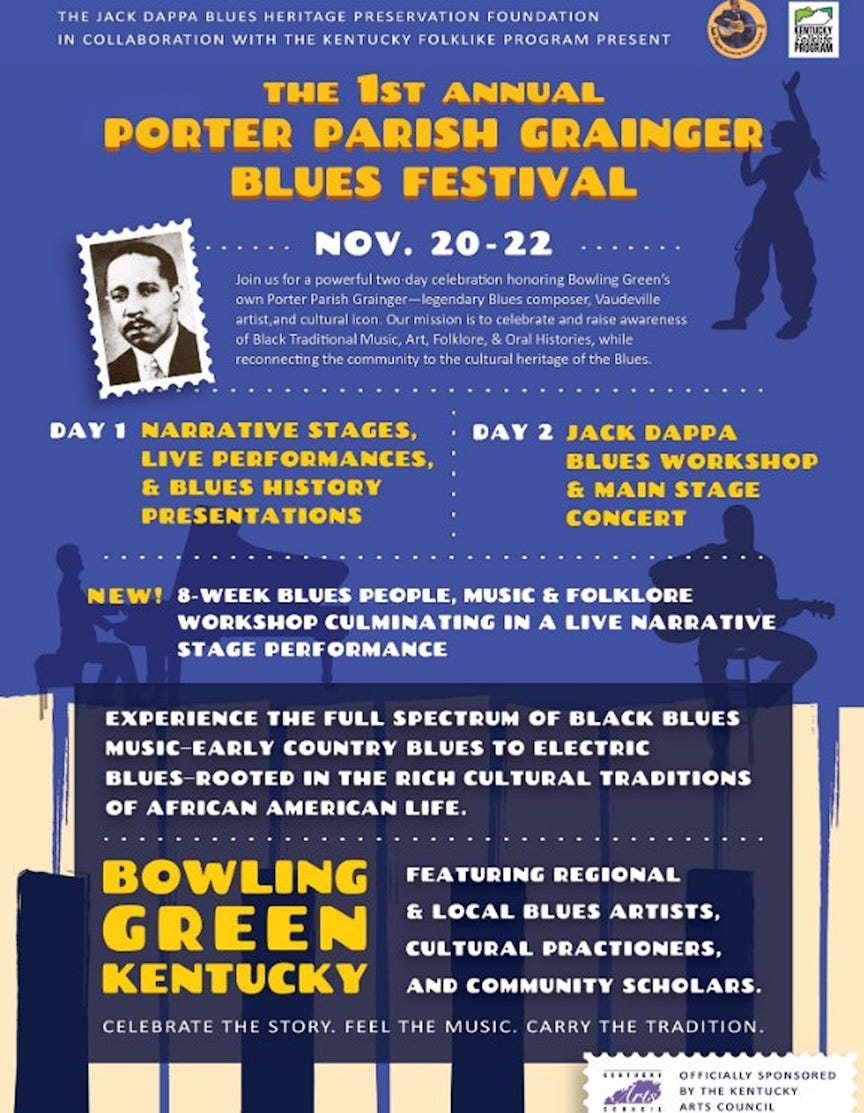

| The lower half of page 29 of the Atlanta Constitution newspaper, Sunday, July 14, 1895. |

I wish I was in Dixie; Hooray hooray!

In Dixie Land I'll take my stand

To live and die in Dixie

Away, away. away down south in Dixie

"Dixie" was a Confederate battlecry in the march against the Union. It had not been composed as a battle song, though.

Daniel Decatur Emmett (1815-1904) premiered this song for a minstrel show a couple of years before the American Civil War broke out. As I documented in I Went Down to St. James Infirmary, while he was not the first blackface minstrel, Dan Emmett created the minstrel show (with his Virginia Minstrels) around 1841. At that time he wrote what is probably the United States' first homegrown popular hit, "Old Dan Tucker."

Audiences usually assumed that minstrel songs were either original "negro songs," or written in the "negro style." Really, most were probably modified Irish ballads and jigs. The lyrics were printed in a sort of vernacular, to reflect speech patterns of the slaves. For instance, "I wish I was in the land of cotton / Old times there are not forgotten ..." was written as, "I wish I was in de lan ob cotton / Ole times dar am not forgotten ..."

Two years after its composition, Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter and the Civil War was underway. The song, already popular, caught on like wildfire. Confederate soldiers, inspired by the thrilling strains of the chorus, rushed into battle "to live and die in Dixie."

Much of the lyric had changed in those two years. Racial references were erased, four-line stanzas became two-line stanzas, and the song's comic patter became racially indiscriminate. It had migrated from a "comic" minstrel stage performance into a folk song.

Regarding this, the July 14, 1895 edition of the Atlanta Constitution newspaper explained that, "the words of the song have undergone many additions and modifications during the thirty-six years of its existence, but a pencil copy in the author's own hand gives the following as the original version, as sung in New York in 1859."

And so we read, in one of the original verses, "In Dixie lan' de darkies grow / 'Ef white fo'kes only plants der toe / Dey wet the groun' wid 'backer smoke / An' up de darkie's head will poke / I wish I was in Dixie, etc."

Incredibly (a sad comment on the times they lived in) the article praised the lyrics as having considerable value: "Those who seek for literary excellence in the homely rhymes will be disappointed, but recognition of the author's design gives the key to their merit, and one sees in them unsurpassed reproduction of negro thought and versification."

"Unsurpassed reproduction of negro thought and versification." How could anyone, reading the lyrics, have even thought that, much less published it in a newspaper??

Although Emmett could be an absurdist (as illustrated by these lines from "Old Dan Tucker:" "Old Dan Tucker was a mighty man / Washed his face in a frying pan / Combed his hair with a wagon wheel / Died with a toothache in his heel"), his lyrics were often uncommonly denigrating (again, from "Old Dan Tucker": "Tucker on de wood pile - can't count 'lebben / Put in a fedder bed - him gwine to hebben / His nose so flat, his face so full / De top of his head like a bag ob wool").

Here are two contemporary (and necessarily sanitized) versions of the two songs mentioned here. First, Bob Dylan, from his film Masked and Anonymous:

And Bruce Springsteen, from a 2006 tour:

In each case, double-click to receive the full-frame video.

%2016x12x72.jpg)